Equity vs. Equality | The Difference, and Why It Matters

Once you’ve worked in the social-impact space for some time, you tend to become familiar with the terms equality and equity—especially if you’re part of a workplace diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) team.

Although similar-sounding terms, equality and equity actually refer to two very distinct concepts, and the differences between these concepts matter greatly to the people in your organization and to the populations you serve.

What is equality?

Equality indicates a system where everyone has the same opportunities and resources—a “one size fits all” approach to human rights. At first blush, equality might seem reasonable: a class where every student has the same course materials and is graded by the same standards, or a workplace where everyone is held to the same expectations.

The catch with equality, though, is that even if everyone gets the same opportunities, they’re not starting from the same place. And even if expectations are the same, people may need different resources to meet these expectations. As the Annie E. Casey Foundation has said, equality is only effective if everyone has the exact same needs, which is rarely the case in the real world.

In a classroom, for instance, a student learning English as a second language might struggle to keep up with assignments and lectures that are all in English. In a workplace, a single parent responsible for childcare might not be able to dedicate long hours to a project the way their child-free colleagues more easily could.

Equality-based treatment may even penalize people for the different obstacles they face. The student might get a lower grade despite hard work, and the parent might be passed over for promotions because they don’t seem dedicated.

In organizational initiatives, equality may play out as a commitment to multiculturalism or “service to everyone”—which, again, sounds like a worthwhile goal. But this goal overlooks the fact that every group has different needs. A networking event for young Black professionals might not be considered “equal” or “multicultural” since it’s not open for all to attend, but it still fulfills a crucial function.

And when programs are designed for a certain population, like a discussion group for teens who identify as LGBTQ+ or a health clinic for unhoused local residents, they don’t have to serve everyone; they’re targeted toward specific communities for a reason. Programs that give everyone equal access to these resources may diminish the positive impact for communities that really need them, eventually becoming ineffective.

If you prioritize equality in your programming, what you’re probably really going for is equity—a different system that’s more difficult to achieve.

What is equity?

Equity is a system that recognizes each person has different resources and opportunities and seeks to understand and provide what people need based on these differences. According to Merriam Webster, equity is a kind of justice that includes “freedom from bias or favoritism.” Paula Dressel, founding vice president of JustPartners, Inc. and the Race Matters Institute defines equity as “treating everyone ... justly according to their circumstances.”

Equity, unlike equality, acknowledges different populations face different barriers to success and works to limit or eliminate these barriers.

As you might imagine, equity is harder work than equality. To return to the classroom example, it’s simple for a teacher to copy the same syllabus and course materials for 20 college students. It’s tricker and more time-consuming to make the materials accessible to students with visual impairments, negotiate deadlines for students with learning disabilities, and explain concepts like office hours to students who haven’t spent much time in a college environment.

These accommodations can make the classroom equitable, rather than equal, since everyone gets resources tailored to their circumstances, and it gives all students a better chance of succeeding in the course.

What else might equity look like in a school or workplace? Here are just a few examples:

- A mentoring program exclusively for women of color

- An after-school tutoring program that allocates more staff and supplies to underfunded schools

- Allowing working parents to set their own schedules based around child-care obligations

- A seminar designed for first-generation college or graduate students

Working toward equity and justice

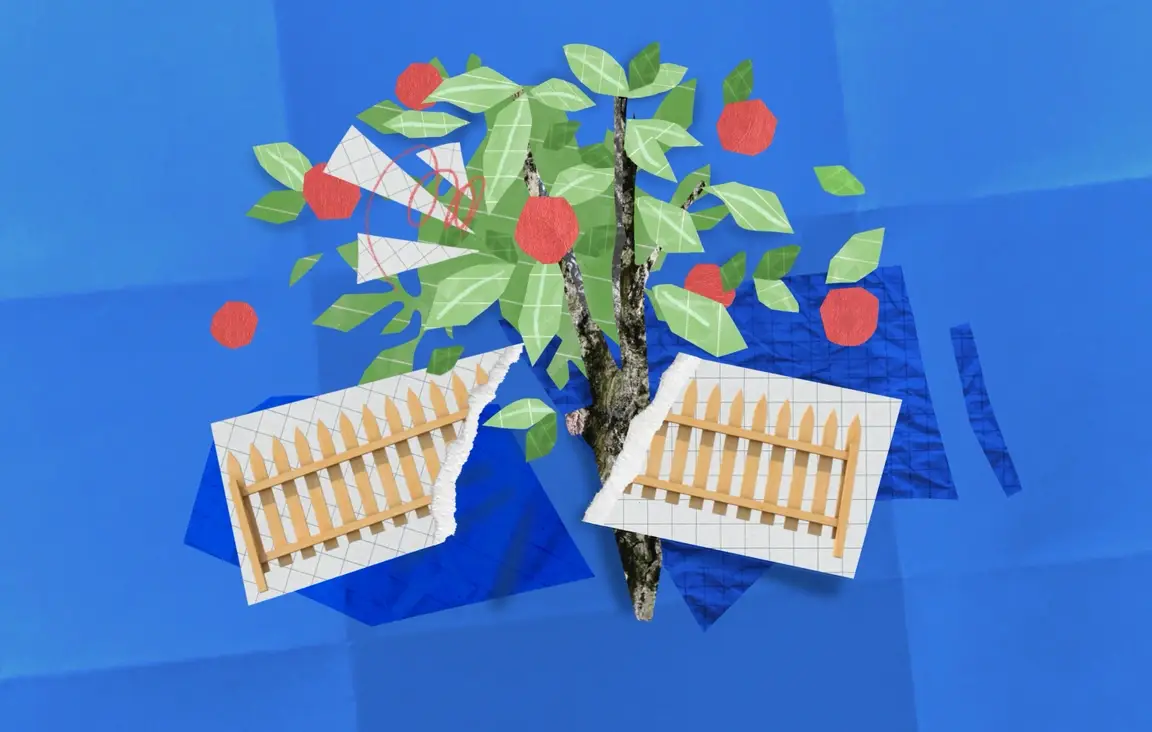

You might be familiar with a graphic that uses two pictures to illustrate the equality/equity difference. In the “equality” image, three people of different heights observe a sports game from behind a tall fence. They’re all equally positioned, but only the tallest person can see the game. In the “equity” image, the two shorter people have wooden blocks to stand on, enabling them to see over the fence.

Like most broad metaphors, this one is imperfect—as writers at the Equity in Education Coalition have pointed out, the image implies the shorter people are to blame for their own unequal circumstances. Even equity-based systems can fall into this trap; organizations may operate on the false assumption that “people of color are less than and, thus, need more,” as the Equity in Education Coalition article says.

Organizations working toward equity might also unintentionally engage in “deficit thinking,” a thought process that holds people responsible for the disadvantages they face.

Justice, on the other hand, focuses on the systemic barriers that prevent people from reaching their goals, not characteristics of the people themselves. When a “justice” image is added to the graphic above, the fence itself disappears. The problem wasn’t that the observers were too short, but that the system was set up for them to fail. And the systemic change, unlike the individual fixes, is permanent—all future observers can now enjoy the game.

Justice as a long-term goal

Achieving justice won’t be a quick fix but a long-term endeavor that affects every aspect of your work. Specifically, organizations can examine how policies, cultural norms, and hiring and promotion practices support or hinder equitable opportunities. Returning to the workplace examples above, your organization could ask:

- Have we created an environment where women of color can flourish and feel like their ideas are being heard? Are they well-represented at all levels, including the executive level?

- Who is working to advocate for underfunded schools on a policy level, and how can we support their efforts?

- How flexible are our parental leave and remote work policies?

- What ongoing financial, logistical, and emotional support are first-generation students offered throughout the semester?

Questions like these won’t be answered overnight, and the answers may require you to rethink, even overhaul, some organizational systems. A mindset that values equity over equality—examining what different populations need and working to empower them, rather than seeking to meet everyone’s needs the same way—will make it easier to see what changes are required. Ultimately, the work should help you live out your DEI ideals as a workplace with justice in mind.

***

Do you have any additional insights on equity vs. equality? Let us know on Facebook!

Amy Bergen is a writer based in Portland, Maine. She has experience in the social impact space in Baltimore, Maryland, the educational museum sphere in Columbus, Ohio, and the literary world of New York City.